In September 2014, representatives from three organizations; Portland Street Art Alliance (PSAA), Endless Canvas (Bay Area, CA) and Graffiti Defense Coalition (GDC) (Seattle, WA) participated in a panel discussion exploring the use of graffiti as a tool for communication and activism.

UNMEDIATED ACCESS & COMMUNICATION IN SPACE

The event was held at the University of Oregon in Portland, as part of the Cascade Media Convergence, a three-day long regional gathering of community-based media organizations, journalists, and artists.

The panel discussion focused on what activism graffiti is, how it can be an effective tactic, how it’s spatial and social contexts affect its message and impact, and how city municipalities and corporations have responded to these types of actions.

The panelists were first asked how they define “graffiti” for the purposes of the discussion.

Occupy graffiti, Portland 2011. Photo: Portland Street Art Alliance

Although each panelist’s definition differed, consensus was that graffiti should be framed both legally and culturally. Legally speaking, graffiti is any marking text, or imagery that’s done in public (private property or public city-owned space) without permission. One type of illegal marking, is activist graffiti, which aims to communicate a dissenting message to the larger public. It was noted by panelists that all of these definitions are fluid and not universal. What is, or is not, considered graffiti greatly depends on the cultural, spatial, and legal contexts within which it is created and viewed.

The panelists then discussed how graffiti exercises our rights to free speech and expression.

Make Living Space Cast out Investors, Berlin September 2011. Photo: Portland Street Art Alliance

Panelists felt that graffiti is a highly autonomous and democratic mode of communication. Because it occurs in public, graffiti is a way for a wide range of people that might not typically interact with one another, to freely and directly communicate with one another. The anonymity acts as a mask, protecting people from being prosecuted (unless caught) and encourages honesty and harsh criticism.

Endless Canvas representatives pointed out that graffiti is an accessible medium for anyone, no matter what their socio-economic status is. Everyone can, at least in theory, create graffiti in public space. In so doing, graffiti can give value and power to under-served parts of society because it’s a way to insert their voice and presence into spaces where they’re otherwise not welcomed or allowed.

Anti-Ulises Ruiz Ortiz graffiti, Oaxaca 2006. Photo: Itandehui Franco Ortiz

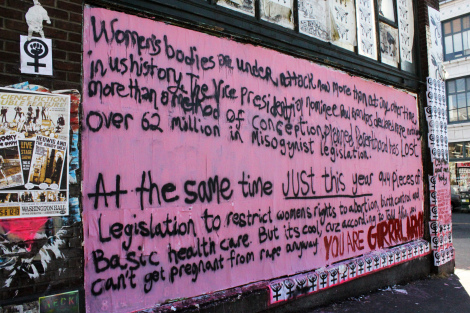

Women’s Rights graffiti by Grrrl Army, Seattle 2012. Photo: Portland Street Art Alliance

Graffiti also challenges so-called “free speech zones,” acting outside of these regulated spaces and pushing the boundaries of what is done and tolerated in public space.

Next, panelists provided examples of how graffiti has been used as a tactic for activism and direct action.

Occupy graffiti, London 2011. Photo: monevator.com

Protest graffiti has been used in countless social movements throughout history. Recent examples can been seen in the Occupy, Egyptian, and Greek uprisings of 2011, the 2006 Oaxaca, Mexico protests, and the 2014 anti-World Cup graffiti in Brazil.

“In our home, our own freedom, our own strength and our own truth.” Kyiv, Ukraine April 2014. Photo: Magdalena Patalong

The multiplying power of social media technologies can amplify the reach of these social and political commentaries. Therefore, these types of unregulated communications can have an immense amount of potential power that governments fear. Governments have been known to shut down telecommunications during political uprisings (for example, in Venezuela, Ukraine, and Egypt).

Memorial Mural for Victims of Police Brutality Oakland, 2013. Photo: Endless Canvas

Violations of free speech like this can even be seen in the U.S. For example, Endless Canvas representatives explained that following the fatal shooting of Oscar Grant by a BART police officer in

Oakland, BART shut down all underground cell phone service to try to prevent large protests. In some cases, graffiti is one of the only ways people can communicate dissenting messages to the public.

Billboard graffiti, Berkeley 2009. Photo: Craig Cook

Also discussed was how graffiti is often used to protest the “visual pollution” of corporate advertising. One of the most interesting cases presented was how Bay Area graffiti writers concentrated their interventions on certain billboard advertisements. These pieces tended to last longer on billboards than other spaces in the city because they were in hard-to-reach spaces, which proved to be difficult for the billboard company to remove. The owners eventually found these billboards to be a lost cause and were decommissioned due to unprofitability. Though the graffiti writers were unconsciously making a political statement, other guerilla artists found that these tactics were a powerful way for average people to fight against corporate advertisements in public space.

It was also pointed out by one panelist that after the AK Media (now Clear Channel) vs. City of Portland case of 2005, painting murals without official city permission in Portland was (and still could be) seen as a form of protest. Today, all murals that are done without a permit or RACC waiver can be reported as “illegal graffiti,” fined, and forcefully removed by the city (regardless of whether or not the property owner consents).

Art Fills the Void by Gorilla Wallflare, Portland. 1982. Photo: Gorilla Wallflare

Kickin Ass for the Working Class by Nuclear Winter, May 1 2011. Photo: Endless Canvas

Panelists were then asked how permitted activist art differs from un-permitted activist graffiti.

Anti-GMO mural in Oakland by Pancho Peskador and Desi W.O.M.E, April 2012.

On one hand, panelists saw both legal and illegal activist art as two different strategies that can work simultaneously. Both forms can communicate powerful messages to the public though political commentary, making an impact on civic consciousness.

On the other hand, panelists also pointed out that it is impossible to radically change the system by working within it. Some believe illegal activist art is a much blunter weapon that maintains maximum power and impact. With illegal art, there is no censorship. It is not mediated through the framework of capitalism or the state and the risks artists take to trespass and produce their artwork illegally infuses their art with intrinsic symbolic power.

Occupy Walls by Graffiti Against the System (GATS), Portland 2011. Photo: Portland Street Art Alliance

Lastly, panelists were asked to think about the public’s reactions to graffiti and how it alters our perceptions of space in the city.

Falsas Promesas Broken Promises, South Bronx, 1980. Photo: John Fekner

A Graffiti Defense Coalition representative gave the example of New York City in the late 1970s when many young people saw graffiti as a creative way to bring much needed color to the crumbling and decaying city, exciting the urban landscapes around them. Amidst this political and infrastructural chaos, authorities and the media began to campaign against graffiti, associating it with dirt, decay, disease, and madness. These anti-graffiti campaigns cited the “broken windows theory” as their basis, arguing that minor misdemeanors (like graffiti) must be stopped or there will be an atmosphere of lawlessness that will attract serious criminal offenders who will assume that residents don’t care about the neighborhood.

By promoting a culture of unrealistic fears, and tapping into the public’s moral insecurities, authorities were able to justify increased policing and regulations of our public spaces. Policing ideologies like this did nothing to address the longstanding social inequalities, infrastructural neglect, purposeful arson-for-profit scams, and declining tax revenues that were causing urban decline at this time. Today, it’s clear to see that graffiti is often actually a sign of a vibrant urban area, or one that’s in the early stages of gentrification (Berlin, Bushwick, and Miami, etc).

Portland Street Art Alliance members then pointed out that dominant ideologies define what is, and is not appropriate in public spaces. In the case of graffiti, the public was told by city-sponsored anti-graffiti ads and public announcements that they should prevent graffiti at all costs, that it didn’t belong in the city, and will cause a spiral of decay like is seen in extremely neglected and ignored urban neighborhoods, like the South Bronx in the 1970s and 80s. Subsequently, the tide of fear and criticism against graffiti rolled in.

Representatives of Endless Canvas echoed the sentiment, stating that graffiti doesn’t actually physically hurt anyone, and the battle between the city and graffiti artists, is a sign of a much larger battle for control, voice, and representation.

Graffiti is considered a major urban problem because it challenges the notion of private property, and by extension, the entire system in which modern society is built upon. It also makes us think about who really does or should have control of our public visual space. It is symbolic of a much larger struggle for our collective rights to the city.

Special thanks to Brett Peters for helping to write this article and CMC organizers, particularly Tim Rice, for supporting and making this regional discussion possible.