GRAFFITI POLICE FORCE ARTIST TO BUFF OWNER-AUTHORIZED MURAL

On Monday August 12, 2013, the City of Portland was about to have a new and exciting addition to its public art collection. Cannon Dill, a highly regarded artist from San Francisco was visiting Portland. He is known for incredibly detailed black and white aerosol murals of enchanting wolf-like creatures and his murals can be seen in cities across the country, including Chicago, Detroit, Denver, Oakland, Brooklyn, Kansas City, Minneapolis, and New Orleans. His artwork is usually welcomed and celebrated as invigorating dull walls and dilapidated urban environments. However, to our dismay, it was met with contempt in Portland by police.

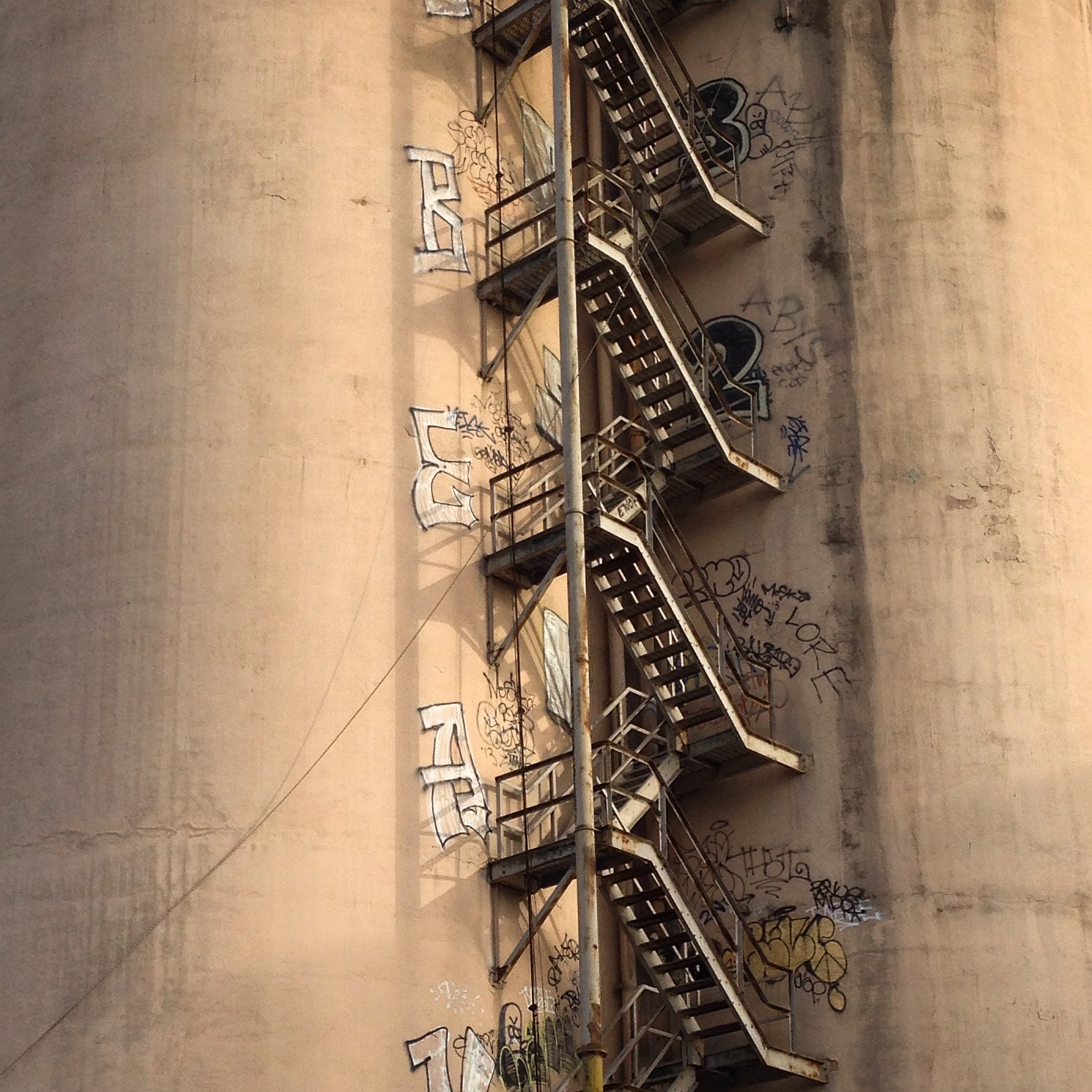

About a quarter of the way through painting a self-funded mural on the side of a chronically tagged building in inner Southeast Portland (SE 9th and Ash) Dill was interrupted by two City of Portland police officers.

The building owner, who arrived at the scene shortly after, immediately expressed their satisfaction with the progress and told the officers that they had given Dill permission to paint the mural. The owner explained that they were trying to deter repeat graffiti tagging. Over the years, they have spent a lot of public tax dollars and time painting over unwanted markings.

After realizing that Dill’s mural was not un-authorized ‘graffiti’ and was instead an owner-authorized mural, the Portland Police officers seemed to be appeased. At that point, in most cities, the situation would have been over and the artist would have been allowed to continue. But in Portland, painting a mural is not that easy.

Shortly after, officer Anthony Zanetti, one of the Portland Police Department’s two Graffiti Abatement Task Force officers arrived at the scene. Officer Zanetti said that due to the lack of proper permitting the mural had to be removed immediately or the building owner would be issued a City citation and fined as being a Graffiti Nuisance Property. In Portland, both private and business property owners can be fined (up to $250 per incident of graffiti) and even jailed if there’s graffiti on their property for more than 10 days after they are issued a citation. This can be quite a burden on small businesses and residents.

Zanetti continued to explain to the owner, that his permission did not matter; they still needed a $250 permit from the Regional Arts and Culture Council (RACC).

While it’s true that the property owner’s permission does not matter in the eyes of the City of Portland when it comes to painting art on the outside of buildings, other things officer Zanetti is reported to have said are not accurate.

Going through RACC is not the only way to paint a mural in Portland. The City has an Original Art Mural Permitting Program, which in most cases, costs only $50 (as of 2013, $56 as of 2022). RACC does provide mural artists exceptions to the city sign codes (providing an easement and adding the mural to the city’s public art collection), but that process is free, and if approved, RACC will actually provide an opportunity to “match” an artist’s mural funding up to $10,000 via an application and review process.

Why did officer Zanetti give the owner inaccurate information? At minimum, we should hold those accountable whose job it is to abate graffiti and and enforce mural regulations to know and provide the public factual information about these rules and processes.

This is also surprising because the City’s new Graffiti Abatement Program Coordinator, Dennis LoGiudice, recently said that he was not going to make regulating non-permitted community murals a priority in his office, which works in partnership with the two Graffiti Task Force police officers.

Zanetti also told the owner that those who do graffiti hide their ‘crew signs’ in their pieces. At the 2013 Graffiti Abatement Summit this past May, Officer Matt Miller (the other Portland Graffiti Task Force police detective) said he and his partner focus their efforts on ‘gang’ graffiti.

The City of Portland estimates that 13-15% of reported cases in the city are ‘gang-related’ (a number we haven’t seen updated by the task force since 2006). However, this estimate is biased and unreliable because it is not systematic and only includes reported cases (and not all cases). It’s also a relatively small proportion compared to other cities. A good amount of Portland’s actual gang graffiti is on the edges of the city, not in the inner-city.

Cannon Dill’s artwork is not ‘gang’ related. He is an artist who mainly paints permission murals and shows his work in galleries. It’s a stereotype that all young people who put their work in the streets (especially those who use aerosol paint and are ethnic minorities) are members of gangs or crews. The main function of these ‘crews’ Zanetti is referring to is to network, share information, organize street art-related events, and paint large murals in cities. All of these tasks take organization and management. Associating artists with criminal gangs (or crews) is often used a fear tactic by authorities to demonize artists and justify more graffiti abatement (in the form of graffiti nuisance property, criminal mischief, vandalism, and trespassing fines). This is a self-reinforcing cycle, the more graffiti ‘problems,’ the more job security for graffiti abatement officials.

One of the main purposes of police officers, in general, is to enforce property laws meant to control access and conduct in public space (or spaces viewed from public space). As soon as you put art in this realm, it is regulated and controlled for us, and not by us.

The fact that the City of Portland requires mural permits is often unknown to visiting artists because in most cities (Seattle and San Francisco for example) there are no permits required for murals and all you need is owner-permission. Neither Cannon Dill, nor the property owner, knew that a mural permit was required. Also, visiting artists often are not able to navigate these permitting processes because it can take anywhere from one to three months to complete and requires someone being physically present to organize and attend neighborhood meetings and post proposed mural site notices.

The situation on Monday afternoon concluded with Dill being forced to buff his mural with white paint. Dill was then told by police to get out of town.

This incident is yet another example of the current problem Portland faces with creating art in public spaces. We’re missing out on showcasing local and visiting artists’ work in our city.

Less than a week after the in-progress mural was forcably buffed, Cannon Dill's only other existing mural in Portland was buffed. The wall and surrounding area along MLK Blvd has had street art and graffiti on it for many months (if not years), with no action from graffiti abatement. This mural was the only piece buffed. It survived for only one week. This was not random buffing, it was a targeted effort to remove all traces of Cannon Dill’s art from the Portland landscape. While we understand that this was in some ways inevitable, since a city mural permit was not attained, we rarely see this type of stealth, targeted abatement.

These incidents are not the first time the Portland’s Graffiti Abatement officers have shut down grassroots efforts to beautify the city with murals. They have targeted numerous galleries, community groups, and other mural efforts over the years (i.e., the Special Delivery gallery show in 2011 and the Samo Lives Gallery in 2012). These situations portray Portland as being an unwelcoming city for public creativity; something other cities are fully embracing.

It seems that many of these threats and shutdowns are also solely aimed at artists working with aerosol paint. For many artists, aerosol is not just a cheaper and easier way to paint large works, it provides a certain aesthetic quality that other mediums cannot replicate.

Even more concerning is that our access to public space in Portland is under siege. Countless barriers are in place that makes it difficult for people to navigate and receive proper permission to paint a mural or otherwise improve our shared public spaces. By systematically denying the city’s diverse artistic possibilities, authorities are increasingly working to encode privilege and exclusion in our public spaces by setting up legal and environmental barriers that make these spaces off-limits to us. If we’re not careful, Portland will turn into a ‘Disneyfied’ version of its former weird and quirky self.

While community art is closely monitored and regulated, countless un-permitted corporate advertising signage across the city is unregulated – something the city could profit from if proper resources were dedicated to corporate signage enforcement.

In difficult financial times, when city budgets and important social programs are being slashed, why does the City continue to use public resources and tax monies on an aggressive graffiti abatement task force that pursues, intimidates, and prosecutes street artists instead of violent criminals?